There are no photographs of that day, which is probably just as well. Photos would have shown a sorry scene: a 7-year-old boy walking alone across the tarmac at the Havana airport, sadly climbing the stairs to an awaiting plane, disappearing through the doorway.

That boy was me, and the year was 1961. My mother and father were sending me, their only child, away from Fidel Castro’s Cuba. My plane was filled with unaccompanied children. Some were excited; others, like me, cried out to parents who could not hear them. I didn’t understand why this was happening to me.

After a short flight, I found myself on another tarmac, this time in Miami. I was led into a terminal where a customs official stamped my passport “INDEFINITE VOLUNTARY DEPARTURE.” There was no one there to meet me. I sat alone in the lounge of a very alien place. Not until then did I realize I had lost my most prized possession: a toy train I had brought to the Havana airport with me. I retraced my steps to customs, but the doors were shut.

Scared and disheartened, I made my way back to the lounge, where I found the family who would be taking care of me. I stayed with them for three long, tearful months before my parents were able to join me in the U.S.

Only years later would I learn why I was forced to start a new life. I was one of more than 14,000 Cuban children sent to the United States by their parents between 1960 and 1962 to protect us from indoctrination in government schools. The mass exodus, run through the auspices of U.S. religious welfare services, would become known as Operation Peter Pan.

Once my parents arrived, we began our American life. I had three tasks: to study, get good grades and, in keeping with the times, assimilate. We still loved our language and culture, but we shared them only at home. Years passed. I earned a degree in geography, got my dream job as a cartographer at the National Geographic Society, married an Irish-German lass and raised a family.

Busy as my life became, though, Cuba never seemed far away, especially when I visited my parents. On those days when the sky was at its bluest, my mother would always remind me, “It’s bluer in Cuba.” She hadn’t seen the Cuban sky since 1961, but she kept it near to her heart until the day she died.

In 2001, National Geographic asked me to lead a tour group to the island. We visited places I had visited with my parents as a child. The mogotes — dome-shape hills emerging from the flat valley floor — in Viñales were smaller than I had remembered, while the Caribbean looked just as transparent as ever. Before leaving, I looked up to heaven and told my mother: “You were so right — the sky is bluer here.” And I started to cry, not so much for what I had forgotten, but for what I had remembered.

Juan José Valdés with his cousins Mayda and Miguel, whom he had not seen in more than 50 years — Courtesy of Juan Jose Valdes

Still, on that trip I stuck with my tour group. I did not have the fortitude to connect with Cuban people or my extended family — the people I’d unwillingly left behind. On a second tour over a decade later, I went to see our former house and even knocked on the door. But when an old man answered and invited me inside, I froze. I couldn’t go in.

In 2013, I had another chance. And this time, things were different. I talked to every Cuban I could and danced with every Cuban woman who gave me the chance — bailar es olvidar penas (“to dance is to forget one’s sorrows”). And I screwed up my courage and drove back to my childhood home.

The old man was still living there, and this time, I accepted his invitation to come in. It was as if time had stood still. I didn’t know this man, but he had kept all of my family’s belongings. I saw my grandmother’s sewing machine in the hallway and my aunt’s framed portraits of Spanish maidens on the dining room wall.

Later that afternoon, I reunited with my cousins Mayda and Miguel, whom I had not seen in more than 50 years. We talked about childhood pranks and listened to an old, familiar album, the sound track from Around the World in 80 Days.

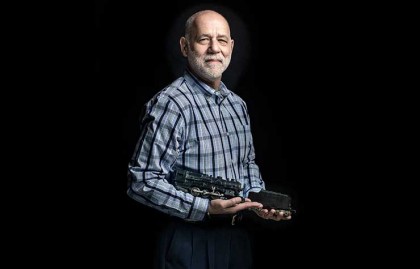

Then Miguel presented me with a ghost from my past: my beloved toy train. It had never been lost, after all. My father had slyly taken it from me at the airport back in 1961. When he left Cuba, my father gave the train to his brother — Mayda and Miguel’s father — telling him that someday I would return for it. Before my uncle’s death, he had given the train to Miguel and told him to keep it for me. And now, I had it in my hands.

No words were needed between Miguel and me. My cousin had honored his father’s wishes, and I had regained a missing piece of my life.

The next day, friends saw me off at the airport. This time, photographs attest to my “indefinite voluntary departure.” Among them there’s a picture of a middle-aged man with a toy train in his hands. And if you look at the picture in just the right way, you’ll also see the beaming face of the 7-year-old boy standing by his side.

Juan José Valdés, 61, lives in Maryland. This story is excerpted from Journeys Home: Inspiring Stories, Plus Tips & Strategies to Find Your Family History.

Source: Journeys Home