Some of the his most under-appreciated contributions are on the relationship between everyday life and the built environment.

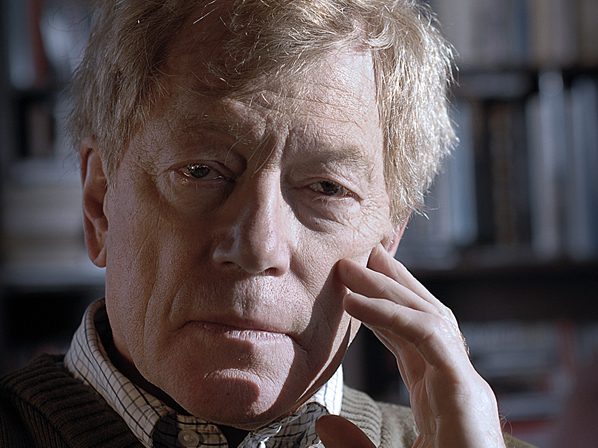

Very few of us will ever be referred to in the adjectival form. Yet Roger Scruton (1944-2020) deserves such an appellation, and as early as 1985, “Scrutonian gusto” appeared in a snide 1985 Architectural Review piece. The Oxford English Dictionary does not yet list “Scrutonian,” though it cites Sir Roger’s heroes, those who follow “Kantian” and “Hegelian” philosophy; “Burkean” is oddly absent, but his intellectual enemies, such as “Sartrian” and “Marcusian,” are also there. Had Sir Roger only been one of the leading philosophers of aesthetics of the past century, “Scrutonian” would have aptly described the spirit of his work. Still the more notable wordplay on his surname came some time later, when Sir Roger himself began referring to his farm as “Scrutopia,” an amusing but memorable neologism that would go on to become a summer school at his rural Wiltshire retreat, drawing many visitors from far beyond British shores.

If it were only for sheer skill in marketing, coining Scrutopia was a masterstroke. A web search suggests that far more writers have now utilized the word Scrutopia than the dryer, more academic Scrutonian references one finds. And one hopes that Scrutopia lives on, not merely as a summer school or a farm, but also a way of experiencing the world, whether in the built or natural environment. To be Scrutopian is a way of identifying, preserving, and creating beautiful places. For as much as Sir Roger was a scholar of aesthetics, art, music, sex, and conservatism, early on in his career he began dedicating much of his time to improving architecture and urban life.

Others in Britain had spoken out before he came of age—notably the poet John Betjeman and journalist Ian Nairn—but no more articulate spokesman for conserving the built environment has emerged since Scruton came to the fore in the 1970s. There were also Americans, such as urbanist Jane Jacobs and novelist Tom Wolfe, who made us care about cities and architecture; Scruton later influenced conservatives across the pond, and indeed around the world. This Scrutopian movement began before it was self-conscious, and is likely to outlive its greatest exponent, but it began with a revolutionary thesis—and started an argument with the architectural establishment that continues today.

♦♦♦

In The Aesthetics of Architecture, his landmark 1979 treatise, Scruton argued that building design is a deeply moral enterprise, and not only about engineering functional or utilitarian structures. The prominent Chicago architect Louis Sullivan had promoted the dictum that “form follows function,” and since then, architects were led down a path toward subjective taste, with no ability to judge comparative aesthetic qualities. Was a 1960s Brutalist-style tower really no better or worse than an 18th-century Georgian terrace of townhouses?

Scruton was frustrated that “[c]ontemporary architects often speak of ‘design problems’ and ‘design solutions’”; they “attempt either to banish aesthetic considerations entirely, or else to treat them simply as one among a set of problems to be solved.” He found that architects seemed so enthralled with abstract theories that they refused to account for other factors, and so he aimed to prove that “aesthetic judgement is an indispensable factor in everyday life.” Still another key ingredient is something akin to Edmund Burke, T.S. Eliot, and Russell Kirk’s “moral imagination,” with Scruton insisting that “in imaginative experience, reasoned reflection, critical choice and immediate experience are inseparable.” It was critical that “aesthetic judgement maintains an ideal of objectivity, and moreover a continuity with the moral life.”

As the 1980s dawned, and the acolytes of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan turned the West to the Right, Scruton was not convinced that conservatism was primarily defined by “market solutions,” as important as it was to contain the ever-expanding state and win the Cold War. In this move toward hyper-individualism, Scruton worried that some libertarians, drawing on legendary economist F.A. Hayek’s theories, were claiming that no city or town planning was necessary. While he celebrated the origins of “spontaneous order,” and was particularly drawn to Jane Jacobs’s “sidewalk ballet” of the urban street, he thought it “dangerous” to forgo any effort to maintain a larger order. Hayek’s ideas showed that “civil society” was important in creating “tacit knowledge,” but now that an established order was in place, “a conscious effort must be made so as to defend [it]” when it “can no longer defend itself.”

Thus the quality and tone of Scruton’s work had turned increasingly from that of the academic to the public intellectual. In highlighting the importance of “public space,” his work appeared in Irving Kristol’s influential U.S. journal The Public Interest in 1984, and years later became part of a collected volume of essays, The Classical Vernacular: Architectural Principles in an Age of Nihilism. This anthology moved from aesthetic theory to more concrete engagement with public policy, and became an annoyance to some on the Right, including Hayekian types. But another new threat on the horizon—postmodernism—was already appearing on metropolitan skylines and streetscapes. The high modernism and International Style of the early-to-mid 20th century had begun to wane, and much of it was replaced with whimsical ornamental references to the past. (The most symbolic was perhaps the 1984 former AT&T Building in Midtown Manhattan, with a pediment atop the 37-floor tower that evoked something akin to a Chippendale highboy dresser.) Scruton was appalled: “To appropriate the classical attributes as surface decoration, without the discipline involved in using them as the shaping principles of architectural thought, is to go one stage further along the nihilistic road of modernism.”

What was the alternative? Scruton’s “classical vernacular” is not a style, or just an aesthetic preference, but a way of building that is both universal and suited to particular places and moments in time. The use of “vernacular” evokes living language. Indeed, he is at pains to show that vibrant places should draw on both tradition and unchanging human nature to create buildings and streetscapes in which we feel at ease and at home. “The classical idiom,” he writes, “does not so much impose unity as make diversity agreeable.” This sense of defining and protecting varied shared communities is at the heart of the Scruptopian project. He most often of course celebrates the English landscape (and its villages, towns, and cities), but has also written movingly of the destruction of the traditional architecture of the Middle East, in part due to the West’s military meddling and utopian scheming.

The Scrutopian does not merely pine for the pastoral, but also aims to make a humane metropolis. Architects can adopt new forms of technology, not for wholesale reinvention—consider the innovation of steel girders and beams that made many large buildings and bridges possible—while still respecting a sense of place and time, as Scruton explains:

In the early age of the skyscraper the new iron-framed buildings took care to show themselves rooted into the street, with detailing that created a street-level façade and a clear relationship to neighbours and to the sidewalk. Such buildings rose joyfully into the air, and were slotted into the sky with attractive hats and crowns that overcame their bluntness. Even when made of mass-produced moulded parts, like the Woolworth Building in New York, with its cast gothic panels, they appeared to be properly composed of those parts, and stood to attention in the public square as though waiting to be acknowledged and approved. I don’t say that the result was an unqualified aesthetic success, still less a collection of masterpieces. Nevertheless the skyscraper idiom was an attempt to resist the habit that succeeded it, of draping steel frames with glass or alloy panels, like Mies in the Seagram building and all the hundreds of faceless blocks that followed his lamentable example.

Before the skyscraper era was the 19th-century age of the railroad, and even during an age of greed and inequality, public architecture reached new heights under the Victorian and Beaux Arts stations. The harried passenger was nevertheless uplifted, pointing to beauty—not only utility. Unlike the featureless superhighways of our time, at least the railroad tried to enhance existing settlements, as Scruton suggests: “The architecture of its stations, viaducts and railway furniture did not degrade but on the contrary enhanced the visual amenity of the landscape and was pleasantly integrated into our cities and towns…” This is why so many fought to save New York’s demolished classical Penn Station, and why the most significant historical landmarks are preserved and repurposed, even when their original purposes are outmoded: “…pace [Louis] Sullivan, when it comes to beautiful architecture, function follows form. Beautiful buildings change their uses; merely functional buildings get torn down.”

♦♦♦

Scruton had begun his first architectural treatise by concluding “that some ways of building are right, and others…wrong.” It was a somewhat abrupt full stop, though one appreciates the expression of moral clarity. There was of course more to be said, and approaching what would become his final decade, by then well established finally at home, in his own Scrutopia, he brought something else increasingly to the forefront. For Scruton, in the end, the end itself—for architecture, art, music, love—was always beauty.

Scruton’s 2009 book, Beauty, reads as somewhat less focused on winning arguments, and perhaps more desperate to convince others that beauty must persevere—and in so doing save civilization. It is about more even than Western civilization, as he takes time to articulate why promoting the classical vernacular is neither hostile to the West, nor is it an attempt to be imperialistic, or merely an affirmation of the bourgeois. Sound philosophy is found in many other societies: “The distinctions between means and ends, between instrumental and contemplative attitudes, and between use and meaning, are all indispensable to practical reasoning, and associated with no particular social order….it is by no means unique to that place and time.”

Yet while we can appreciate cultures outside our own, we cannot become cosmopolitans. Human nature, he says, is such that “[o]ur need for belonging is part of what we are, and it is the true foundation of aesthetic judgment.” To find beauty, we must in some sense settle, and truly be at home—in our neighborhood, city, or region. The odd fact is that all forms of beauty are on a continuum, so for most of us who are not engaged in creating great works of art, but in “everyday life,” Scruton calls for us to find harmony, not strike a discordant note: “In the case of urban design, for example, the goal is, in the first instance, to fit in, not to stand out.”

To some reacting to this today, it immediately sounds like totalitarianism, or in less loaded terms, stifling creativity. Yet another way to respond to such a first principle of “fittingness” is a posture of modesty. This is also unpalatable in our secular world, where freedom is defined by maximum individual fulfillment, and there is little room for the virtues inspired by Christian  humility. Notably, in Beauty, Scruton himself never explicitly moves into the theological realm, but concludes that “rational beings,” do have freedom, and that they can choose a “path out of desecration towards the sacred and the sacrificial.”

humility. Notably, in Beauty, Scruton himself never explicitly moves into the theological realm, but concludes that “rational beings,” do have freedom, and that they can choose a “path out of desecration towards the sacred and the sacrificial.”

To find and create this sense of the sacred in your everyday life—particularly in your little patch of the world, and then other places radiating outwards—is what it means to be Scrutopian. If it sounds almost like a “new age” self-help book, then perhaps some who quickly dismissed Scruton as an old, conservative reactionary might even now reconsider their hostility. And as many continue reading and rereading Scruton’s work, it will help refine the terms of public discourse, keeping intellectual conservatism vibrant and relevant. Scruton’s name might not appear as a deserved adjective in the dictionary, but his work will continue to provoke important conversations—and identify transcendent experiences, especially for anyone striving to live in beautiful places.

Lewis McCrary is formerly executive editor at The American Conservative. This New Urbanism series is supported by the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation.

This post originally appeared on and written by:

Lewis McCrary

The American Conservative 2020-08-15 04:01:00