The sordid history of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS)

The legal immunities of the supranational bank perpetuates the belief that the central bankers are unaccountable to everyday citizens and their own governments. The bank does not reveal the discussions at their meetings with the central bankers of the world or its internal operations. The bank has no accountability or transparency in its operation.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) was created on May 17, 1930 to administer or “settle” the World War I reparations imposed on Germany under the Treaty of Versailles. There were four very powerful individuals who played a very important role in the founding of BIS: Charles G. Dawes, Owen D. Young, Hjalmar Schacht, and Montagu Norman.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) was created on May 17, 1930 to administer or “settle” the World War I reparations imposed on Germany under the Treaty of Versailles. There were four very powerful individuals who played a very important role in the founding of BIS: Charles G. Dawes, Owen D. Young, Hjalmar Schacht, and Montagu Norman.

Adam Lebor wrote the best and most up-to-date book on BIS called Tower of Basel: The Shadowy History of the Secret Bank that Runs the World (2013). This book is the first investigative history of the most secretive and powerful global financial institution in the world. Lebor conducted many in the interviews with international central bankers and their employees, including Paul Volcker, the former chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank (the Fed), and Sir Mervyn King, former governor of the Bank of England. He also conducted extensive archival research of the BIS in Basel, Switzerland and other libraries in the United States and Great Britain. His book included biographies on the major central bankers who founded the bank and the important officials that worked at BIS.

James C. Baker was the author of a pro-BIS book entitled The Bank for International Settlements: Evolution and Evaluation (2002). This author wrote a comprehensive history of BIS.

Gianni Toniolo with Piet Clement wrote a book entitled Central Bank Corporation at the Bank for International Settlements 1932-1973 (2005). These two professors wrote the history of BIS from 1932 to 1973.

Carl Teichrib contributed to an article or report entitled “Global Banking: The Bank for International Settlements” prepared by The August Forecast and Review, which was published on October 14, 2005. The article presented a comprehensive history of the creation of BIS and a short biography of the founders and history of BIS up to 2005. Edward Jay Epstein wrote an article about the BIS in Harpers Magazine in 1983. He described the BIS as the “most exclusive, secretive, and powerful supranational club in the world.”

In spite of these three excellent books and many articles, the BIS is completely unknown by the vast majority of the American people. This most powerful supranational bank has always wanted to keep a low profile. Even well-known authors who have written books describing the history of the operations of the Federal Reserve Bank as well as the powerful organizations

that run the United States and the world, such as the Bilderberg Group, the Trilateral Commission, and the Council of Foreign Relations, do not even mention the existence of the BIS. This is surprising as the owners and employees of the banking cartels who own the central banks of almost all the Western nations, including the United States, are all involved in the BIS. This international bank is the central bank of all the central banks in the United States and Europe, as well as other nations in the world.

The four individuals who were instrumental in the creation of the Bank for International Settlements are the following:

· Charles G. Dawes. He was the director of the United States Bureau of the Budget in 1921 and later served on the Allied Reparation Commission in 1923. His subsequent work on stabilizing the German economy won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1925. Dawes was elected vice president under President Calvin Coolidge from 1925 to 1929. Two years later, he was appointed ambassador to England. In 1932, he resumed his banking career as chairman of the board of the City National Bank and Trust in Chicago, where he remained until his death in 1951.

· Owen D. Young. He was an industrialist who founded the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) in 1919 and served as its chairman until 1933. Young became chairman of the board of General Electric from 1922 to 1939. He tried to obtain the nomination as president of the Democratic Party but lost to Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932.

Young became chairman of the board of General Electric from 1922 to 1939. He tried to obtain the nomination as president of the Democratic Party but lost to Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932.

·  Hjalmar Schacht. He served as president of the Reichsbank of Germany from December 22, 1923 to January, 1939. He was responsible for the economic recovery of Germany that allowed Adolf Hitler to rearm the German Armed Forces and lounge World War II.

Hjalmar Schacht. He served as president of the Reichsbank of Germany from December 22, 1923 to January, 1939. He was responsible for the economic recovery of Germany that allowed Adolf Hitler to rearm the German Armed Forces and lounge World War II.

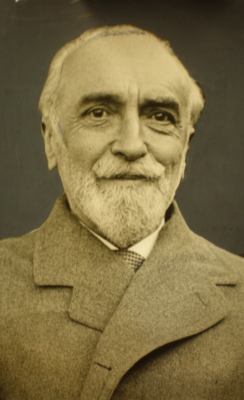

· Montagu Norman. He served as the governor of the Bank of England from 1920 to 1944. During those years he was one of the most influential central bankers of the world. His power was so enormous that a single speech made by Norman could affect the New York Stock Exchange in the United States and other stock exchanges the world. Before and during World War II, Montagu Norman allegiance was to the Bank of International Settlements and not to Great Britain.

the world. His power was so enormous that a single speech made by Norman could affect the New York Stock Exchange in the United States and other stock exchanges the world. Before and during World War II, Montagu Norman allegiance was to the Bank of International Settlements and not to Great Britain.

The Versailles Treaty of 1919 that ended World War I imposed on Germany a heavy burden of reparations. It required that Germany to comply with a payment schedule of 132 billion gold marks per year. Germany was bankrupt and suffering from hyperinflation following the war and was unable to pay the enormous war reparations dictated by the Versailles Treaty. In 1924, the Allies, or the nations that defeated the German Empire, appointed a committee of international bankers led by Charles G. Dawes and his assistant Owen Young to develop a plan to help Germany with the reparation payments. It was decided that $800 million in foreign loans have to be arrange for Germany in order to rebuild its economy.

Dawes was replaced by Owen Young in 1929, so now the Dawes Plan became the Young Plan. Carl Teichrib contributed to an article entitled “Global Banking: the Bank for International Settlements” which was published on October 14, 2005 by the August Forecast and Review. He explained the following: “Neither Dawes nor Young represented anything more than banking interests. After all, World War I was fought by governments using borrowed money made possible by the international banking community. The banks had a vested interest in having those loans repaid.”

Hjalmar Schacht, the President of the German Reichsbank, and Montagu Norman, the Governor of the Bank of England, came up with the idea of creating a new bank free from politics that could assist with Germany’s payments to the Allies. The need to establish such a bank for this purpose was suggested in 1929 by the Young Plan.

On January 20, 1930, the governments of the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Belgium, Italy, Japan, and Switzerland signed a document that became known as the Hague Agreement. Article 1 of the Hague Convention or Agreement stated that “Switzerland undertakes to grant to the Bank for International Settlements, without delay, the following Constituent Charter having force of law: not to abrogate the Charter, not to amend or add to it, and not to sanction amendments to be Statutes of the Bank referred to in Paragraph 4 of the Charter or otherwise than in agreement with the other signatory governments.”

Article 10 of the Hague Convention or Agreement stated that “the bank, its property and assets and all deposits and other funds entrusted to it shall be immune in time of peace and in time of war from any measure such as expropriation, requisition, seizure, confiscation, prohibition or restriction of gold or currency export or import, and any other similar measures.” Thus, the powerful BIS was born as a result of this international treaty.

According to Adam Lebor, Gianni Toniolo with Piet Clement, and James C. Baker, authors of books regarding the history of the Bank for International Settlements, this supranational banking institution was created with unprecedented powers and privileges. The central bankers who created the BIS held politicians with contempt, the exception being if the politician was one of their own. The BIS founders wanted to build a transnational financial system that could move large amounts of capital free from political or governmental control. The central bankers demanded and received incredible immunity from their own governments, free from any type of regulation, scrutiny, or accountability for the BIS directors and members as well as their employees.

The unprecedented immunity that was granted was the following:

· Diplomatic immunity for persons and what they carry with them, such as diplomatic pouches.

· Not being subjected to taxation on any transactions, including salaries paid to employees.

· Embassy-type immunity for all buildings and/or offices operated by the BIS.

· Freedom from immigration restrictions.

· Freedom to encrypt any and all communications of any sort.

· Freedom from any legal jurisdiction.

· Immunity from arrest or imprisonment and immunity from seizure of their personal baggage, except in flagrant cases of criminal offense.

· Immunity from jurisdiction, even after their mission has been accomplished, for acts carried out in the discharge of their duties, including words spoken and writings.

· Exemption for themselves, their spouses, and children from any immigration restrictions, from any formalities concerning the registration of aliens, and from any obligation relating to national service in Switzerland.

· The right to use codes in an official communications or receive or send documents or correspondence by means of couriers or diplomatic backs.

On February 10, 1987, the BIS and the Swiss Federal Counsel signed a “Headquarters Agreement” which confirmed the immunities previously granted to the BIS when it was created, as well as additional immunities. Article 2 stated that “the Bank buildings shall be inviolable… No agent of the Swiss public authorities may enter therein without the express consent of the Bank… The archives of the bank and, in general, all documents and any data media belonging to the Bank… shall be inviolable at all times and in all places. The Bank shall exercise supervision of an police power over its premises.”

Article 4 of the Headquarters Agreement stated the following: “The Bank shall enjoy immunity from criminal and administrative jurisdiction, except to the extent that such immunity is formerly waived in individual cases by the president, the general manager of the Bank, or their duly authorized representative. The assets of the Bank may be subject to measures of compulsory execution for enforcing monetary claims. On the other hand, all deposits entrusted to the Bank, all claims against the Bank and the shares issued by the Bank shall, without the prior agreement of the Bank, be immune from seizure or other measures of compulsory execution and the sequestration, particularly of attachment within the meaning of Swiss law.” In essence, the 1987 Headquarters Agreement granted the BIS similar protections given to the headquarters of the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, and diplomatic embassies.

On February 27, 1930, the governors of the central banks of Germany, Great Britain, France, Italy, and Belgian met with representatives from Japan and three American banks to establish the Bank for International Settlements. Each nation’s central bank purchased 16,000 shares. Since the Federal Reserve Bank was not permitted to own shares of BIS for political reasons, three United States banks, the First National Bank of New York, J. P. Morgan, and the First National Bank of Chicago, created a consortium and each bank purchased 16,000 BIS shares. Thus, the United States representation at the BIS was three times as that of any other nation.

This international bank’s initial share capital was set at 500 million Swiss francs. The owners of BIS purchased 200,000 shares of 2,500 of gold francs. The governors of the founding central banks were ex-officio members of the board of directors and each could appoint a second director of the same nationality. Many years later, on January 8, 2001, an Extraordinary General Meeting of the BIS approved a proposal that restricted ownership of BIS shares to central banks. At the time, 13.7% of all shares were in private hands. BIS set a price of $10,000 per share which was over twice the book value of $4,850. Some private owners of the BIS shares filed a lawsuit against the bank insisting that the shares were worth much more money than what was offered.

At the beginning, central bankers wanted to keep a very low profile and complete anonymity for their activities. The first headquarters of the BIS was an abandoned six-story hotel, the Grand et Savoy Hotel Universe, with an address above the adjacent Frey’s Chocolate Shop, near the train station at Basel, Switzerland. No sign was placed at the door identifying the BIS. In May 1977, however, the BIS moved to a more visible and efficient headquarters. The new building was an 18-story circular skyscraper that arises

over the medieval city of Basel, Switzerland and soon it became known as the “Tower of Basel”. The new building is completely air-conditioned and self-contained. It has a nuclear bomb shelter in the basement, a private hospital, and some 20 miles of subterranean archives. From the top floor of the Tower of Base there is a panoramic view of Germany, France, and Switzerland.

During the war years, the BIS continued operating from its headquarters in Basel, Switzerland. Adam Lebor explained that “during the war, the BIS became a de-facto arm of the German Reichsbank, accepting looted Nazi gold and carrying out foreign exchange deals for Nazi Germany.” The alliance of BIS with Germany was known in the United States and Great Britain. However, the need for the bank to keep functioning in order to maintain transnational financial operations was agreed by all the countries that fought each other during World War II.

Lebor pointed out the following: “A few miles away, Nazi and Allied soldiers were fighting and dying. None of that mattered at the BIS. Board meetings were suspended, but relations between the BIS staff of the belligerent nations remained cordial, professional, and productive. Nationalities were irrelevant. The overriding loyalty was to international finance.” During the war years, an American, Thomas McKittrick, was president of the bank. A Frenchman, Roger Auboin, was the general manager and a German, Paul Hechler, was the assistant general manager and a member of the Nazi party. An Italian, Raffaelle Pilotti, was the Secretary-General, a Swedish, Per Jacobssen, was the Bank’s economic advisor; and other employees were British.

Since the time that Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933 and to the end of World War II in 1945, five German members of the board of directors of the BIS were Nazis. After World War II they were convicted of war crimes. These BIS directors were the following:

· Hjalmar Schacht, who was the architect of the economic recovery of Germany and served as the Reichsbank President until 1939.

· Hermann Schmitz, the Chief Executive Officer of IG Farben, a gigantic German chemical conglomerate that during the war built and ran a factory of synthetic rubber using prisoners as slave laborers at the concentration camp at Auschwitz.

· Walther Funk, who replaced Hjalmar Schacht at the Reichsbank and who was a member of the Nazi party since 1931. He worked for the SS Chief Himmeler.

· Baron Kurt von Schröder, the owner of the J.H.Stein Bank, a bank that held the deposits of the Gestapo.

· Emil Puhl, who was vice president of the Reichsbank bank.

During the Nuremberg trials that followed the end of World War II, 104 Germans were sentenced to death or to prison terms. Those who received terms in prison included four of the five directors of the BIS. Hermann Schmitz was sentenced to four years. Walther Funk, who had worked with Himmler, the SS chief, to ensure that gold and valuables from the Jews at the concentration camps were credited to a special account at the Reichsbank, was sentenced to life imprisonment. Baron Kurt von Schröder was tried by a German court for crimes against humanity and sentenced to three months in prison. Emil Puhl was sentenced to five years. As for Hjalmar Schacht, he was found guilty but then he was acquitted since he had been sympathetic to the Allies in the early years of the war.

During the Nuremberg trials that followed the end of World War II, 104 Germans were sentenced to death or to prison terms. Those who received terms in prison included four of the five directors of the BIS. Hermann Schmitz was sentenced to four years. Walther Funk, who had worked with Himmler, the SS chief, to ensure that gold and valuables from the Jews at the concentration camps were credited to a special account at the Reichsbank, was sentenced to life imprisonment. Baron Kurt von Schröder was tried by a German court for crimes against humanity and sentenced to three months in prison. Emil Puhl was sentenced to five years. As for Hjalmar Schacht, he was found guilty but then he was acquitted since he had been sympathetic to the Allies in the early years of the war.

After the war during the Bretton Woods conference held in New Hampshire in July 1944, Norway proposed the liquidation of the BIS at the earliest possible moment for assisting Nazi Germany to deposit the stolen gold from the occupied nations that it had conquered in the bank. The liquidation of the bank was supported by other European delegates as well as the United States delegates who included Harry Dexter White and the Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau. However, the liquidation of the bank was never actually undertaken. In April 1945, the new United States President Harry S. Truman and the British government suspended the dissolution of the bank. The decision to liquidate the BIS was officially reversed in 1948.

How does the Bank of International Settlements operate today?

The BIS is a bank for all the central banks of the major nations in the world. According to the website of the Bank for International Settlements, the mission for this international bank is to serve central banks in their pursuit of monetary and financial stability, foster international cooperation in those areas, and act as a bank for central banks. The BIS pursues its mission by:

· Promoting discussion and facilitating collaboration among central banks.

· Supporting dialogue with other authorities that are responsible for promoting financial stability.

· Conducting research on policy issues confronting central banks and financial supervisory authorities.

· Acting as a prime counterparty for central banks in their financial transactions.

· Serving as an agent or trustee in connection with international financial operations.

The headquarters of the bank remain in Basel, Switzerland and there are two representative offices, one in Hong Kong and the other one in Mexico City. Acting as the central bank, the BIS has sweeping powers to do things for its own benefit or to assist one of its members central banks. Article 21 of the original BIS statute defines the day-to-day operations as follows:

· buying and selling of gold coin or bullion for its own account or for the account of central banks;

· holding gold for its own account under reserve in central banks;

· accepting the supervision of gold for the account of central banks;

· making advances to or borrowing from central banks against gold, bills of exchange, or other short-term obligations of prime liquidity or other approved the securities;

· discounting, rediscounting, purchasing or selling with or without its endorsement deals of exchange, checks, and other short-term obligations of prime liquidity;

· buying and selling foreign exchange for its own account or for the account of central banks;

· buying and selling negotiable securities other than shares for its own account or for the account of central banks;

· discounting for central banks bills taken from their portfolio and rediscounting with central banks bills taken from its on portfolio;

· opening and maintaining current or deposit accounts with central banks;

· accepting deposits in connection with trustee agreements that may be made between the BIS and governments in connection with international settlements.

Organization and governance of the Bank for International Settlements

The bank currently employs 647 staff members from 54 countries. The three most important decision-making bodies within the bank are: the general meeting of members central banks, the board of directors, and the management of the bank. The BIS currently has 60 members central banks, all of which are entitled to be represented and to vote in the general meetings. However, voting power is proportionate to the number of BIS shares issued in the country of each member represented at the meeting.

At present, the board of directors of the bank has 19 members. The board has six ex officio directors, made up of the governors of the central banks of Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom and the chairman of the Board of Governors of the US Federal Reserve System. Each ex officio member may appoint another member of the same nationality. The rest of the board of directors is made up through the election of nine other governors from members of central banks. The governors of the central banks of Canada, China, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, and the president of the European Central Bank are currently elected members of the board of directors.

The board of directors of the Bank for International Settlements is responsible for determining the strategic and policy directions for the bank, supervising the management, and fulfilling this specific tasks given to by the bank´s statutes. The board meets six times a year.

Edward Jay Epstein explained the major beliefs of the inner circle of the BIS. The members of the board of directors have the firm belief that central banks should act with complete independence of their own governments. Another belief is that politicians should not be trusted to decide the fate of the international monetary system. The powerful central bankers of the world share a preference for pragmatism and flexibility over ideology. The most important belief is that they cannot allow a central bank of a large country to fail, for fear that it could jeopardize the entire international monetary system due to interconnectedness with the central banks of other nations. This is a result of globalization and interdependence.

History professor Carroll Quigley from Georgetown University wrote a book entitled Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in our Time (1966). This professor was a mentor of President Bill Clinton. Professor Quigley was very familiar with how the international bankers operated in the world. He happened to agree with their goals. Professor Quigley wrote the following: “I know of the operations of this network because I have studied it for 20 years and was permitted for two years, in the early 1960s to examine its papers and secret records. I have no aversion to it or to most of its aims and have, for much of my life, been close to it and to many of its instruments.”

Dr. Quigley described the international banking network in the following manner: “The powers of financial capitalism had another far-reaching aim, nothing less than to create a world system of financial control in private hands able to dominate the political system of each country and the economy of the world as a whole. This system was to be controlled in a feudalist fashion by the central banks of the world acting in concert, by secret agreements arrived at frequent private meetings and conferences. The apex of the system was to be the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland, a private bank owned and controlled by the world’s central banks which were themselves private corporations. The key to their success, was that the international bankers would control and manipulate the money system of a nation while letting it appear to be controlled by the government.”

The founder of the most powerful banking dynasty in the world, Mayer Amschel Bauer (who later adopted the name Rothschild) said in 1791 “allow me to issue and control a nation’s currency, and I care not who makes its laws.” Four of his five sons were sent to London, Paris, Vienna, and Naples to establish a banking system that would be outside government control. The eldest son stayed at Frankfurt, Germany where the first Rothschild bank had been established. Eventually, a privately-owned central bank was established in almost every country, including the United States in 1913. These banking cartels have the authority to print money in their respective countries and governments must borrow money to pay their debts and fund their operations from them. And of course, at the top of this network is the privately-owned BIS, the central bank of the central banks of the world.

Ellen Brown wrote an article entitled “The Tower of Basel: Secretive Plans for the Issuing of a Global Currency” which was published in Global Research on April 17, 2013. The reporter explained that the British newspaper The London Telegraph had an article entitled “The G-20 Moves the World a Step Closer to a Global Currency.” The British newspaper said that the leaders of the G-20 nations have agreed to support a currency that was created by the International Monetary Fund called Special Drawing Rights or SDR. The leaders of the G-20 nations have activated the power to create money and begin global quantitative easing, which is printing money out of thin air, not back by gold or any other thing. The world is now a step closer to a global currency, backed by a global central banks, running monetary policy for all humanity. The London Telegraph’s article stated that the financial institution that would do this would be the BIS.

There is no doubt that the BIS is moving the entire world to regional currencies and ultimately, a global currency. The global currency could be a successor to the SDR, and may be the reason why the BIS recently adopted the SDR as its primary reserve currency. Canada, Mexico, and the United States are members of the trade group called the North American Free Trade Association (NAFTA). It may be that someday soon a common currency will be used for these three North American nations. It might be called the amero, which will sound like the euro, or some other name such as the NAFTA dollar. The adoption of the common currency is a voluntary surrender of sovereignty and is a step towards a one-world government dominated by these powerful international bankers.

There is no doubt that the BIS is moving the entire world to regional currencies and ultimately, a global currency. The global currency could be a successor to the SDR, and may be the reason why the BIS recently adopted the SDR as its primary reserve currency. Canada, Mexico, and the United States are members of the trade group called the North American Free Trade Association (NAFTA). It may be that someday soon a common currency will be used for these three North American nations. It might be called the amero, which will sound like the euro, or some other name such as the NAFTA dollar. The adoption of the common currency is a voluntary surrender of sovereignty and is a step towards a one-world government dominated by these powerful international bankers.

After World War II, Jean Monnet, a French internationalist, who helped found the League of Nations, had the idea of creating a European Union where nations would relinquish their national sovereignty as an economic necessity. The BIS came up with the idea creating the euro, which eventually was adopted by 17 European countries. The removal of the sovereignty of European nations was presented as an economic necessity, rather than as a profound political process. The powerful elite of international bankers, powerful industrialists with the complicity of government officials, decided to create a one-world government under the United Nations, but controlled by them. Thus, the European Union was born.

The officials and technocrats from the BIS where most instrumental in the creation of the European Union and its currency the euro. They also created the very powerful European Central Bank, a bank that is not accountable to any government or the European Parliament even though, it controls the monetary policy of 17 countries.

The BIS has done very well financially over the years. In 2012, the supranational bank had 355 metric tons of gold and an estimated value of $19 billion. By the end of March 2012, the BIS made a profit of $1.17 billion. Each year the bank makes over $1 billion in profits. The bank makes much of its profits from the fees and commissions that it charges to central banks for its services.

The relationship of BIS with the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) lends money to national governments when these countries have some type of fiscal or monetary crisis. The IMF raises money by the receiving contributions of its 184 member nations. Thus, all of its funds are taxpayer’s money. The World Bank also lends money and has 184 member nations. Within the World Bank are two separate institutions: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, which lends money to middle income and poor countries that have good credit, and the International Development Association, which lends money to the poorest countries of the world.

The BIS, as the central bank to the other central banks, facilitates the movement of money and they provide what is known as “bridge loans” to central banks while waiting for the funds of the IMF and/or the World Bank. For example, when Brazil in 1998 had a currency crisis because it could not pay the enormous accumulated interest on loans made over a protracted period of time, the IMF, the World Bank and the United States bailed out Brazil with a $41.5 billion package. If that nation had not paid its creditors, United States banks such as Citigroup, J.P. Morgan Chase and Fleet Boston would have lost an enormous amount of money. Thus, the real winners of rescuing the largest country in South America were the U.S. banks that had made risky loans.

Criticisms of the Bank for International Settlements

Adam Lebor has made very strong criticisms of the BIS. He said that this bank is an elitist, opaque, and anti-democratic institution which is out of step with the 21st century. The legal immunities of the supranational bank perpetuates the belief that the central bankers are unaccountable to everyday citizens and their own governments. The bank does not reveal the discussions at their meetings with the central bankers of the world or its internal operations. The bank has no accountability or transparency in its operation.

Lebor wrote that the BIS should lose its legal inviolability. It is important that citizens around the world demand more transparency and accountability from the financial institutions that have power over their lives and that includes the BIS. It is very important for Americans to pay attention to the operations of the BIS and our own Federal Reserve Bank since we could very easily lose our sovereignty and be subjected to the desires and wishes of unelected and undemocratic central bankers of the world.